I know, I know. It’s been a LONG while since I last published anything here. I could blame it on grad school, but I stopped adding things to this blog before I dove deep into research, essays, and WAY too much coffee. I could make excuses, but in the end, it comes down to too many things on my mind, not enough creative energy. However, this post isn’t about me. Well, I’m not the main character at least. In previous posts, I’ve given tips on how to research and how to edit one’s work, but it’s time to put my money where my mouth is and take you on my research journey while I look up Dr. Catherine Sheldrick Ross.

Even deciding to do Ross for this Information Behaviour assignment (yes, yes, I AM double-dipping by using this both as blog material and a university assignment) was a journey itself. My professor for the course gave us plenty of time and detail to start this assignment, but here I am just starting to put words to paper three days before it’s due. I originally wanted to interview a professor from another one of my classes, Paulette Rothbauer, because of my interest in Reader Services—

Oh right, I should say what I’m in school for and explain some terminology. I’m working on my master’s degree in library and information science. Information Behaviour is the study of how people find certain information in certain contexts, like how does someone find information for their favourite hobby or how new immigrants get situated in a new country. Reader Services (also called reader’s advisory) looks at how librarians can recommend good books to their patrons. Anyway—

But Professor Rothbauer didn’t think it was a good idea for me to interview her when I was currently taking her for a course, and when I asked about good academic articles on how your average Jo goes about finding new books without librarian assistance, she recommended Catherine Sheldrick Ross. My original idea to make a “research dating profile” then became a little tasteless considering she’d passed away less than a year ago. So now here I am, writing this personal essay on how I found information for an Information Behaviour assignment. Meta, eh?

Academia: A New Lexicon

In The Writer’s Toolbox, I discuss free online tools you can use to research words, reference materials, and how to use the CRAAP test. I’ve learned through other classes that the CRAAP test has its flaws. Fielding (2019) and Wineburg et al. (2020) show that the CRAAP test is only effective at looking at a source without the larger contexts its placed in, making people more susceptible to misinformation. It’s with that in mind I turn to two different sources to evaluate Ross’ academic “stats”: Scopus, and Web of Science. It is important to note that Google Scholar and ORCID are free options to explore the works of academics but they don’t seem to have a profile on Ross. Unfortunately, Scopus and Web of Science are not free, and I’m only able to access them through being a student at Western University, but this offers an opportunity to teach those who may not be in the know about publication metrics.

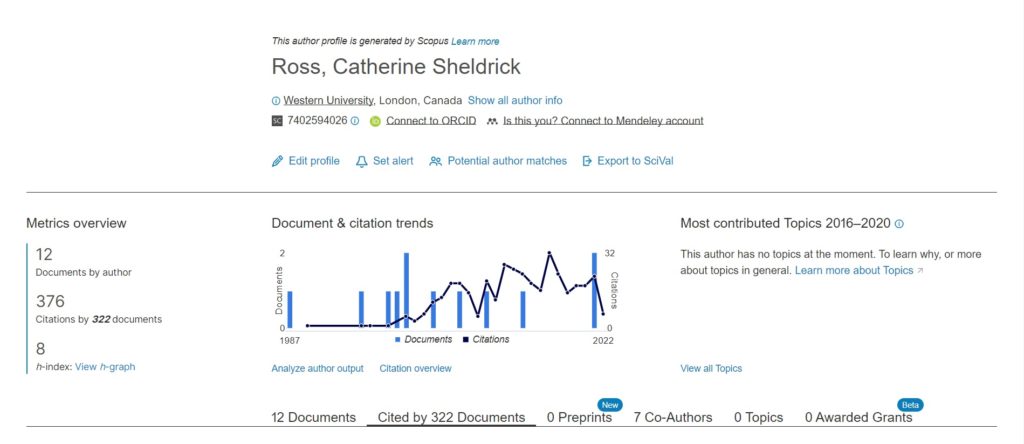

Let’s start with the first thing you see when you look up Ross’ author profile on Scopus:

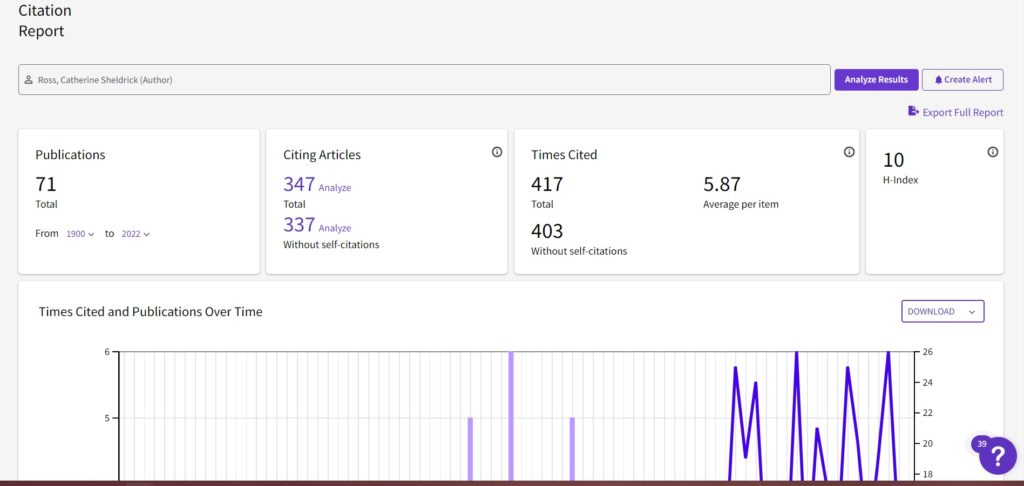

If you’re like me, when you first saw this (in my case in Information Sources & Services with Heather Hill) your first reaction was “what the heck is any of that?” and to be honest, that reaction remains true for me and my colleagues. I’ve talked to doctorate level students who can’t explain what an h-index is, but I’m going to attempt to explain all that here. Let’s compare Scopus to Web of Science:

Now, even if none of this currently makes sense to you, it’s easy to notice some discrepancies. Scopus says Ross has only 12 publications while Web of Science lists 71. Why? While both Scopus and WoS index journals, they have different standards for what gets indexed. Typically, Scopus has breadth while WoS has depth, and the two databases have different citation rates, fields of interest, and types of journal papers they’re interested in (Jyotsana 2018). In comparison, Google Scholar is a search engine, which will appear to have wider coverage because it includes other things such as theses and unpublished material. However, the trade-off for Scopus and WoS being pickier means they focus on papers that have a higher scientific impact (Elesevier 2020). In saying that, Google Scholar remains useful to cross-reference these databases if you’re able.

More importantly, what can we take from this information? Well, with WoS, we can conclude that Ross has at least 71 documents it considers worthy of indexing. The “Citing articles” (in WoS) and “Citations by” (in Scopus) represent the times Ross has cited other articles, while “Times Cited” in WoS represents how many times Ross’ work has been cited. The h-index combines these numbers, measuring “the impact of a researcher or group of researchers rather than a journal,” “for example, an h-index of 28 means there are 28 publications that have 28 citations or more for each” (Western Libraries n.d.). Of course, you might note that this measurement may feel pointless with different databases (be it Google Scholar, Scopus, or World of Science) having different amounts of journals from a researcher but knowing this information may help you contextualize what sort of impact a researcher may have.

What I think this little exercise and shallow dive into the confusing world of publication metrics demonstrates more than anything else is considering not only quantity (something Google Scholar provides) but quality as well, and to make sure to not only consider these elements within your sources but compare them against each other and other sources you might find. For example, while Web of Science lists 71 publications…some of those go back to 1945, which was the year Catherine Sheldrick Ross was born. It’s very possible this Ross (whose work is sometimes published under CS Ross) got confused with a CS Ross that is interested in geology. As I said, looking at all sources beyond what they display is an important part of research.

Catherine Ross the Academic

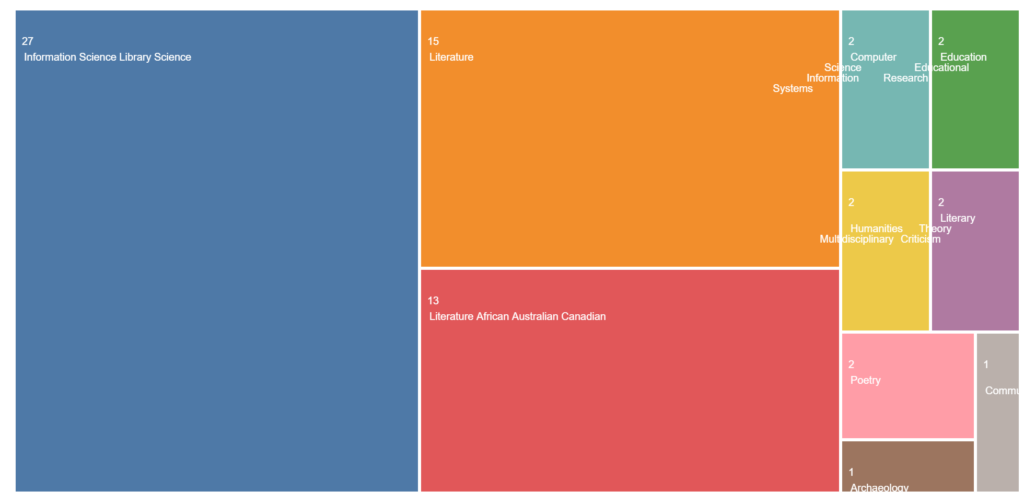

The above is a visualization of what topics Ross has covered through her academic articles from Web of Science (after I had to hand-remove all documents about rocks from when Catherine Ross was a child, leaving 64 publications). These show the different subjects that Ross has focused on in her works, and I find it infinitely more useful for getting an understanding of a researcher than any of the metrics information and why I prefer Web of Science. As one can see, 42% of Ross’ work focuses on “Information Science Library Science” and explains one of the reasons why I frequently run into her papers in my courses, but this and the metrics information only give us a bird’s eye view of a researcher, and we’ll have to dive deeper to understand the work Ross has done. Where could we possibly start for that?

Almighty Wikipedia.

What? You thought “fancy” academics wouldn’t “stoop so low” as to use Wikipedia? No way man, Wikipedia is a goldmine! While Wiki articles themselves may be spotty, their references sections help begin the journey to more credible sources. Starting there, a portrait of Ross begins to be painted.

Ross achieved her BA (with honours) at Western University in 1967, would go to the University of Toronto to get her MA in 1968, and then return to Western to earn her doctorate in 1976 and her Master of Library and Information Science in 1984 (“Catherine Sheldrick Ross,” 2021). Through this, it becomes clear that Ross had a special place at Western, another reason why I frequently ran into her works in class, specifically in Heather Hill’s Information Sources & Services course, particularly when we learned about Reader’s Advisory. Neal Wyatt (2020) discusses her because she created an appeal framework based on interviewing over 300 readers (which is detailed in her 2014 book The Pleasures of Reading (“Catherine Sheldrick Ross”, n.d.)), “addressing why people read, how they select titles, and the elements that contribute to enjoyment” (Wyatt, 2020 p. 438). When having to do a reader’s advisory assignment for Hill’s course, I remember preferring Ross’ framework of appeal to Saricks and Brown’s and Pearl’s because it felt more comprehensive. Appeals are

a set of terms that describes the multiple attractions readers have to books and with the reading experience. More broadly, it is a framework advisors use to translate what a reader enjoys about one book into a set of descriptors that can be applied to others

(Wyatt 2020 p. 436).

Essentially, appeals are elements within books that might attract a reader such as character, setting, pacing, etc. Ross’ appeal system includes: mood, cost, physical size, subject, treatment, impact, character, pacing, action, setting, and ending (Wyatt, 2020). What struck me about Ross’ system compared to Saricks and Brown’s and Pearl’s was that it included appeals that existed outside the contents of books, such as physical size, mood (an appeal that considers how the reader’s mood (whether stressed or calm) affects book selection (Wyatt, 2020)), and cost (addresses the effort it takes to read a book (Wyatt, 2020), whether that’s a mental, emotional, or financial toll). However, academics don’t just publish theories.

For a majority of the time Ross was writing her 64 publications (among others), Ross was a faculty member at Western. As a professor, she taught “graduate courses in reference, research methods, reading and genres of fiction and information needs and uses” (Ross, 2000). She served as “a transitional Dean in the earliest days of [the Faculty of Information and Media Studies’] founding (1996-1998)” as well as during 2000-2002 (as Acting Dean) and 2002-2007 (as Dean) (Western FIMS 2021a). Even after she retired from teaching in 2010, she continued to write and publish up until her death. She published “important texts on conducting reference interviews with readers and library users, reading for pleasure, and communicating professionally” (Western FIMS 2021a). She also was awarded the Reference Service Press Award four times, Novelist’s Margaret E. Munroe Reward in 2013, (American Library Association, n.d.) and the Science Writers of Canada Award for best science book written for children in 1996 (for Squares: Shapes in Math, Science, and Nature) (“Catherine Sheldrick Ross,” 2021). On top of that, she was named a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (Western FIMS, 2018). This isn’t getting into the fact that she’s “presented more than fifty workshops on reference and readers’ advisory to library professionals in the United States and Canada” (American Library Association, n.d.), authored several children’s books and nonfiction books, as well as set up student bursaries in her name (Western FIMS, 2021).

So. Maybe you’re thinking “so a lady wrote a bunch of books and won a bunch of awards, how does this affect me, Joe-Smhoe who hasn’t visited the library in over a decade?” Well, to that I’d say “wow, Brittany, what a Strawman you’ve created to segue into the next section!”

A Deep Dive into 3 Ross Articles

As shown by Web of Science, Ross has offered up many publications in the field of information and library sciences, and it would be difficult to cover all of them in a short personal essay. Instead, I thought I’d do a deep dive into three articles of personal interest. This also helps us learn how to read academic articles, which are, to be honest, often full of bunk. Especially if you’re in grad school, or otherwise have a busy lifestyle in which gathering information quickly is essential, one must adopt a new way of reading. I find Sweeny’s blog post on How to Read for Grad School particularly helpful in that regard, but to cut to the chase: read academic articles strategically in which you scan for important information that applies to you, take notes, and use your brain (er, I mean apply “a critical perspective”) (Sweeney, 2012). With that in mind, let’s dive into the first Ross article:

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. (1999). Finding without seeking: the information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 783- 799. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00026-6

We start with the highest cited publication Ross has listed in both Scopus and Web of Science, being cited a total of 125 times according to Web of Science, making up around a third of all the times Ross has been cited (417). This was a significant paper for Ross and the subject of reader advisory in general. You can view the abstract here.

A lot of times as a grad student, I simply read the abstract and conclusions and move on to the next article, but for you guys, let’s try to look at the articles in their entirety. In Finding without Seeking, Ross took the interviews of “194 committed readers” to analyze “how readers choose books to read for pleasure” and “books that have made a significant difference in readers’ lives” (Ross, 1999 p. 783). The paper concludes that five implications emerge for the information search process: “the active engagement of the reader/searcher in constructing meaning from texts; the role of the affective dimension; `trustworthiness’; the social context of information seeking; and the meta-knowledge used by experienced readers in making judgments about texts” (Ross, 1999 p. 783). I’ll break that down further.

In the basic structure of an academic article, after the abstract (a brief summation), the introduction is the “hook” of the article, the “shots, shots, shots, shots, shots, shots, everyb’dy!” of academia if you will. Here, or sometimes in a “literature review” section, you’ll find citations of articles on similar topics as the one you’re reading, which can be helpful if you’re gathering information on a specific topic. Here, Ross notes that “the research field typically constructs the information-seeker as a person with an articulated question that is formally posed of an information system” (Ross, 1999 p. 785). In short, Information Behaviour (IB) studies focus more on people who have a goal and fully formed questions when they seek information, but this article focuses on situations of information encounters that people have not specifically sought out to more fully encompass how people seek out information every day. In the interviews conducted, Ross focused on “free voluntary reading” (Ross 1999 p. 786) as opposed to reading prescribed for work or school. The analysis relies primarily on these questions:

How do you go about choosing a book for pleasure? Has there ever been a book that has helped you or made a difference to your life in one way or another? [Probes: What difference did it make? How did it help you?] How do you feel about rereading books?

(Ross, 1999 p. 786)

Ross notes that a previous study that used surveys to indicate leisure book selection methods (Spiller 1980) reported: by the author only, 11%; by authors/some browsing, 22%; equal by authors/browsing, 36%; browsing/some authors, 20%, and by browsing, 11% as methods of selection, but that these categories don’t acknowledge “what these strategies mean for the people who perform them” (Ross, 1999 p. 788). Ross goes on to indicate many personal factors interact together when a reader chooses “a good book” to read (Ross, 1999, p.789), with “the bedrock for choice [being] the reader’s mood” (1999, p.790). Examples given for this were:

When readers wanted safety, reassurance, and confirmation, they often reread old favorites or read new books by known authors that they can trust. At other times, they wanted to be amazed by something unpredictable, unexpected, or new. At such times, readers reported that they might pick books on sheer impulse to introduce novelty into their reading and discover new authors or genres.

(1999, p. 790).

Here, we witness a small tidbit that would later impact the creation of Ross’ appeal framework I discussed earlier. In analyzing readers’ statements, five elements that play off each other immerge in the process of readers picking books for pleasure:

- The aforementioned mood appeal

- “Alerting sources that the reader uses to find out about new books (browsing, recommendations from interpersonal sources/reviews of advertisement/lists/serendipity)”

- Elements in the book itself (the more traditional appeal such as characters, setting, and subject)

- “Clues on the book itself used to determine the reading experience being offered (author, genre, cover, title, sample page, publisher)”

- And the aforementioned cost appeal (Ross 1999 p. 791).

Already, Ross has obtained helpful models for understanding how avid readers discover new books for themselves, and this information itself could be extremely helpful in helping librarians access how they can assist library users in finding new books they’ll enjoy, but Ross doesn’t stop there. Ross asked readers “has there ever been a book that has helped you or made a big difference in your life in one way or another? (1999, p. 791), and discovers that, regardless of genre, these books (a) had a narrative form, and (b) could be related to the readers’ own lives (1999). Seven categories of responses to how these books made a significant impact on their lives:

- Affected readers’ perspective

- Characters in books created a model for readers’ identity (i.e., were role models for the reader)

- Readers were validated or comforted by the book’s contents

- Book created a connection with others/helped readers not feel alone

- Book gave readers “courage to make a change”

- Books allowed readers to accept a personal life situation

- “Disinterested understanding of the world” in books impacted readers’ beliefs/knowledge of the world (1999 p. 795)

Ross argues that, painting this picture of how avid readers choose and value books is important for exemplifying “everyday practices of meaning-making” (1999 p. 796) because this type of reading is done for its own sake, void of extrinsic goals. With that in mind, however, Ross notes there are some implications for the information search process:

- “The reader/searcher is actively engaged in constructing meaning” (1999 p. 796).

- Feelings and mood play an important role in the reader/searcher’s “transaction with texts” (1999 p. 796).

- “Readers/searchers give a strong weight to the value of `trust’” (1999 p. 797)

- “Reading occurs within a network of social relations” (1999 p. 797)

- “Experienced readers/searchers have a well-developed heuristic for making choices that depends on extensive previous experience” (1999 p. 797).

There you go, I just broke down a 17-page article into around a thousand words, you’re welcome.

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. (2000). Making Choices: What Readers Say About Choosing Books to Read for Pleasure. The Acquisitions Librarian, 13(25), 521. https://doi.org/10.1300/J101v13n25_02

Making Choices is not listed as a publication on Web of Science. It is listed on Scopus, however. It differs from Finding without Seeking and Reader on Top in that it is a book chapter rather than an academic article. Scopus lists Making Choices only under Finding without Seeking in terms of how many times it’s been cited, so another impactful work. This paper also uses the 194 open-ended interviews that Ross used for Finding without Seeking (Ross, 2000 p. 5), focusing specifically on suggesting a comprehensive model for the process of choosing books for pleasure reading and includes the five elements (the first list of the three I share) discussed above and applies

two further stages of choice: the set of choices that get a particular book home from the library or bookstore and make it available for reading; and the choice to read one book rather than another at any given time.

(Ross, 2000 p. 6)

Ross goes on to state that choice permeates the topic of reading “at every stage” (2000 p.8), and that voluntary reading is significant to developing high literacy, as people who are choosing reading over any other activity are experiencing an inherent pleasure in the reading experience itself. This again affirms the importance of Ross’ work, not only in aiding librarians in finding “good books” to match with readers but promoting high literacy, as those who love reading are effectively teaching themselves, “beginning in childhood” and each “unsuccessful choice decreases the beginning reader’s desire to read, which in turn reduces the likelihood of further learning based on interaction with books” (2000 p.9). Acknowledging this, Ross expands on those five elements from Finding without Seeking, and you can access the abstract through Google Scholar.

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. (2009). Reader on Top: Public Libraries, Pleasure Reading, and Models of Reading: Pleasurable Pursuits: Leisure and LIS Research. Library Trends, 57(4), 632–656.

Reader on Top is in Ross’ top five most cited articles (according to Web of Science), so while it didn’t have the impact Finding without Seeking did, it was nonetheless an important paper. Considering Making Choices, it is the least cited article of the three, but I’ve always been one for an underdog, so let’s dive in.

Instead of analyzing her model, Ross examines other models of reading that have been used by librarians “in their discourse and policy making about pleasure reading” (Ross, 2009 p. 632). Ross acknowledges how these different models place different significance on “the power of the text, the role of the readers, and effect on the reader of what is read” (2009 p. 632). Using two types of readers as test cases (whose reading tastes are historically maligned, the series book reader and romance reader), Ross examines the appropriateness of these models in public libraries. Like the other articles I looked at, you can access the abstract through Google Scholar here. I won’t be dissecting each of the models (“Reading with a Purpose”, “Only the Best”, “The Great Debate”, “The Reader as Dupe”, “The Reader as Poacher”, “Blueprints for Living”, and “The Reader as Game Player”), which were developed by various fields (the first two within public librarianship whilst the others through education, psychology, mass media studies, and sociology) here because I’d affectively be rehashing Ross’ entire article. (Ross, 2009 p. 638). Ross notes that

reading for pleasure is the domain where sharp differences in reading models are thrown into high relief. There is no contest about the value of reading utilitarian and improving works—textbooks, reference books, how-to-do-it manuals, spiritual and religious texts, works of history or philosophy. But reading popular fiction can still raise alarm bells for guardians of public taste.

(Ross, 2009 p. 633)

Thus, it is important to consider different reading models because they are foundational “in arguments about what librarians should think and do about building collections and serving readers” (2009, p.635-6). While the seven reading models I listed above aren’t “entirely distinct” (2009 p.638), they each have unique features despite familial resemblances. Ross asks many questions of these models in consideration of how they construct the role of the reader, how powerful the text is, and how the book affects the reader. For example, “Reading with a Purpose” constructs the reader as someone who reads to learn, and under this model “the ideal reader is a person whose leisure time was productively used to systematic education” and steadily works to improve their literacy skills (2009 p. 639). In this model, reading cannot simply be a pleasure, and if anything, pleasure is a distraction. In this model, “the pleasure reader is judged and found wanting—he or she is faltering in purpose, easily distracted, lazy, and apt to be seduced from the goal of education by the easy allure of popular culture” (2009 p. 640). It is easy to see how, if librarians adhered to only this reading model, how library purchases would be skewed, and historically, it did:

between 1925 and 1933, with funding from the Carnegie Foundation, the ALA developed and sold to readers some 850,000 copies of bibliographic guides on sixty-six different subjects, including biology, economics, geography, farm life, sociology, psychology, the young child, race relations, philosophy, English history, Russian literature, music appreciation, architecture, American education, Latin America, George Washington, and advertising.

(2009 p. 639)

While reports from readers during the 20s and 30s indicated that many viewed the public library as a place for “adult education” (2009 p. 639), if library collections only focus on readers looking to be educated, other types of readers become maligned. Ross voices how much is at stake for public libraries when one chooses one reading model over another and making unexamined assumptions “can be dangerous” (2009 p. 653). Ross asks us when comparing the models to identify

where each locates itself with respect to the following dimensions:

-Agent in charge (reader/text/political economic structure)

-The desired outcome of reading (pleasure/instruction)

-Effect of reading on the reader (beneficial/harmful)

-Process of learning to read (a natural developmental process)/ a specialized process for experts

(2009 p. 654)

In this article, Ross lays out these models and gives you the tools to dissect and engage with them yourself rather than applying her judgements and analysis.

Catherine Ross the Person

Ross was more than just an academic, and that comes out crystal clear when you read pages remembering her on the Western FIMS faculty pages, and her obituary. Her research into reading truly came from a place of passion and want to share her love of reading and learning with her family and beyond (Harris Funeral Home n.d.). Her colleagues list some pieces of advice Ross dispensed to them: “work with people who care about you and your success”, “travel light, with carry-on luggage”, “be ready to give more rope”, and “invite others to join the party” (Western FIMS 2021b), showing someone who loved to live life, and compassionately bring others along for the ride. In her obituary it is stated, instead of flowers, to donate to the Bruce Trail Conservancy “to support a land trust for the protection of natural areas on the Niagara Escarpment”, to the Faculty of Information and Media Studies at UWO “to support graduate education in Library and Information Science”, or to “a charity of your choice” (Harris Funeral Home, n.d.). Even in her early passing at 75 due to biliary cancer on September 11, 2021, her memory promoted goodwill toward nature, a passion for librarianship, and simple empathy.

In her, I see an ideal aspiration and kinship through our shared love of hiking and reading (“Catherine Sheldrick Ross”, 2021). Her work alone was enough to inspire me to dive deep into how I can further help people find the books and other media of their dreams to enhance their love of reading. I can only hope over my academic career to achieve an iota of what this trailblazing woman did.

A Self-Absorbed Conclusion

After first coming across her work through Wyatt (2020), I was in awe of her. Having to read so many articles and books throughout my English and creative writing undergrad and now my masters, I’m loathed to say that most readings get passed over or simply melt into the back of my mind, but not so with Ross’ framework of appeals, which seemed to feel so empathetic about the reading experience of others. Funnily enough, we share a loose connection through the poet James Reaney, who Ross interviewed for The Pleasures of Reading (2014) (FIMS 2021a). I had to read Reaney’s play The Donnellys for an undergrad class (I believe it was Canadian Drama), and later I was a feature poet for the “Voicing Colleen” Event on May 7, 2018 (Colleen as in Colleen Thibaudeau, Reaney’s wife) and got the opportunity to meet Reaney and Thibaudeau’s children, Susan and James. Due to my apartment’s location close to London’s downtown public library where the event was taking place, I hosted the horde of poets, the Reaney siblings, and Peggy Roffey (an English professor at Western) in my tiny apartment so we could rehearse. I nearly overbooked myself and had to sprint home from a shift at Covent Garden Market’s cheese stand (poetry and academia don’t pay, guys) to find that some homeless person a defecated on my front step with less than a half-hour for all these important people to show up. And of course, who was to arrive at my place early but the children of two celebrated poets, seeing me attempting to remove the excrement before anyone arrived. To my embarrassment, James assisted me in doing this and later remarked that his mother (you remember, Colleen Thibaudeau, the person who we were honouring with this event because she’s a local treasure) would have found the entire situation humorous. I never got the honour to meet Dr. Catherine Ross, but I can only imagine that I would have similarly bumbled our introduction, and she would’ve taken it with similar grace, empathy, and humour.

Works Cited

American Library Association. (n.d.). Catherine Sheldrick Ross. American Library Association. https://www.alastore.ala.org/content/catherine-sheldrick-ross

Catherine Sheldrick Ross. (n.d.) ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Catherine-Ross

Catherine Sheldrick Ross. (2021). In Gale Literature: Contemporary Authors. Gale. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/H1000173840/LitRC?u=lond95336&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=d5db9e67

Elsevier. (2020). Why is my citation count on Scopus lower than on Google Scholar. Elsevier. https://service.elsevier.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/30003/supporthub/scopus/~/why-is-my-citation-count-on-scopus-lower-than-on-google-scholar/

Fielding, J. (2019). Rethinking CRAAP: Getting students thinking like fact-checkers in evaluating web sources. College & Research Libraries News, 80(11), 620. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.80.11.620

Harris Funeral Home. (n.d.). Dr. Catherine Ross Death Notice. Harris Funeral Home. http://www.harrisfuneralhome.ca/obits.php?id=2367

Jyotsana. (2018). When to choose SCI Journals over SCOPUS and Vice-versa. Chanakya Research. https://www.chanakya-research.com/when-to-choose-sci-journals-over-scopus-and-vice-versa/

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. (1999). Finding without seeking: the information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 783–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00026-6

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. (2000). Making Choices: What Readers Say About Choosing Books to Read for Pleasure. The Acquisitions Librarian, 13(25), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J101v13n25_02

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick. (2009). Reader on Top: Public Libraries, Pleasure Reading, and Models of Reading: Pleasurable Pursuits: Leisure and LIS Research. Library Trends, 57(4), 632–656.

Spiller, D. (1980). The provision of Fiction for public libraries. Journal of Librarianship, 12(4), 238-265

Sweeney, Miriam E. (2012). How to Read for Grad School. WordPress. https://miriamsweeney.net/2012/06/20/readforgradschool/

Western FIMS. (2018). Catherine Ross named to the Royal Society of Canada. Western University. https://www.fims.uwo.ca/news/2018/catherine_ross_named_to_the_royal_society_of_canada.html

Western FIMS. (2021a). In Memoriam: Catherine Ross. Western University. https://www.fims.uwo.ca/news/2021/in_memoriam_catherine_ross.html

Western FIMS. (2021b.) Remembering our mentor and friend, Dr. Catherine Sheldrick Ross. Western University. https://www.fims.uwo.ca/news/2021/remembering_our_mentor_and_friend_dr_catherine_sheldrick_ross.html

Western Libraries. (n.d.) h-index. Western University. https://www.lib.uwo.ca/researchmetrics/authormetrics/hindex.html#:~:text=The%20h%2Dindex%20is%20defined,Hirsch%2C%202005

Wineburg, Sam, Breakstone, J., Ziv, N., & Smith, M. (2020) Educating for Misunderstanding: How Approaches to Teaching Digital Literacy Make Students Susceptible to Scammers, Rogues, Bad Actors, and Hate Mongers. Stanford History Working Group Working Paper. Working Paper A-21332. https://purl.stanford.edu/mf412bt5333

Wyatt, Neal. 2020. Chapter 21: Readers’ Advisory Services and Sources, In Reference and Information Services: An Introduction, 6th ed., pp.433-463, Melissa A. Wong and Laura Saunders, eds. Santa Barbara. CA: Libraries Unlimited.